International Women's Day: Celebrating our own Dr. Pharath Lim

March 8, 2020

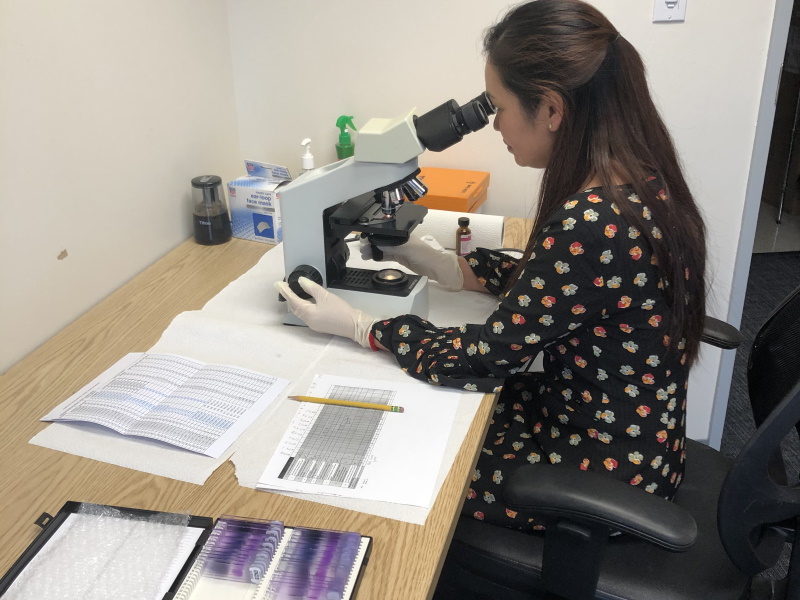

Dr. Pharath Lim.

Dr. Pharath Lim has over 19 years of experience working to combat malaria in resource-limited settings in Africa and Southeast Asia.

She is an expert in malaria diagnostics, treatment, and prevention; surveillance for emerging antimalarial drug resistance; malaria pre-elimination, and elimination efforts. At MCDI, she offers technical and programming support to strengthen health systems (at the national and sub-national levels) in developing countries to ensure high-quality and equitable service delivery in malaria case management.

In honor of International Women’s Day, we interviewed Dr. Lim on her life and accomplishments:

When did you start working for MCDI?

I began working for MCDI on 2 November 2015.

What is your current role at MCDI?

My current role is the Senior Technical Advisor for Impact Malaria project. I provide technical support to strengthen developing country health systems at the national and subnational levels to ensure high-quality and equitable service delivery in malaria case management under “Impact Malaria” – a USAID President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI)-funded project that currently supports 10 countries in Africa (Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, DRC, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Madagascar, Niger, Sierra Leone and Zambia). I also serve as a key technical expert for malaria‘s portfolio at MCDI including malaria diagnostics, treatment and prevention, malaria pre-elimination and elimination, and drug-based resistance monitoring.

What brought you to MCDI?

I discovered MCDI was hiring a malaria diagnostic technical advisor through an advertisement on the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) website, and submitted my application. At that moment, I was in my 5th year of postdoctoral research at NIH in Rockville, MD, and was looking for a job related to my research field in malaria. It was my first job application!

What keeps you working at MCDI?

Because MCDI focuses on malaria, I am able to use my knowledge in this disease to save lives everyday around the world.

What has been the most rewarding aspect of your work with MCDI?

The most rewarding aspect of my work and MCDI’s work, in my opinion, is the fact we get to save lives. Through our efforts, we reduce the mortality rate of malaria and strengthen health systems to ensure as many people as possible receive quality health services such as malaria treatments and diagnostics.

Another rewarding aspect of my work, in my opinion, is having the ability to promote our successes every year at the annual ASTMH Conference and through our published works in several scientific journals.

What did you receive your post-doctorate in?

When I was at NIH, my research was focused on developing phenotypic and molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistant falciparum malaria. We were looking for the different molecular markers related to the artemisinin resistance to falciparum malaria. Our team was the first team that found the molecular marker of artemisinin resistance (published in Nature journal) and piperaquine resistance to Plasmodium falciparum (published in Lancet infectious Disease Journal).

What interested you in that research?

Approximately five million people die from malaria every year in Sub-Saharan Africa, with most being children under 5, as drug-resistant malarial strands render most antimalarial drugs ineffective. My interest in malaria research stems from the desire to ensure people infected with this disease (or have the possibility to be infected with this disease) receive the highest quality treatments.

Before your doctorate, where did you go to school?

I was trained as a medical doctor in my country of Cambodia and graduated in 2000. After finishing medical school, I found my first job at the Institut Pasteur in Cambodia where I started working in malaria research. I then acquired a Masters degree in Biology, Genetic and Immunology of Parasitic Infection at the University Pierre and Marie Curie in Paris in 2004, followed by a PhD in Parasitology at the University Paris Descartes – Paris V, Paris, France in 2009.

Where in Cambodia were you born and where did you live?

I was born near the border of Thailand in the Battambang province, the same area where the chloroquine drug resistance first happened in the 1960’s.

What is your average work day?

My mornings are typically filled with meetings. In fact, through my role at MCDI, I have meetings with country staff from five francophone countries including Cote d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Mali, and Niger. In these meetings, I am backstopping technical supports on various in-field project activities, providing support to in-country teams during execution of day-to-day functions, and planning as well as implementing projects, including setting priorities. The morning then ends with a meeting with the home office and technical team.

The afternoon consists of data analysis and updating. I review incoming reports from the countries (e.g., activity reports, quarterly reports, annual reports), update field teams with new training materials as well as presentations for field staffs, and support the quality assurance system of malaria diagnostic at the health facilities in the countries. Additionally, I contribute to proposal development, planning (e.g., strategic, work, operational), project implementation, setting priorities in technical reports, and reviewing scientific reports as well as abstracts.

I then determine where to publish or promote the information I receive from the reports and meetings – in peer-reviewed journals, or scientific papers, or blogs, or at scientific meetings, or international conferences, etc.

What would you say about your time at MCDI?

My time here at MCDI has greatly expanded my horizons as a scientist. Before I arrived at MCDI I was research-focused, but throughout my time working with vulnerable populations in developing countries, I’ve adopted a more “global health” outlook as well as broadened my expertise to include Africa.

What advice would you give to young women?

The secret to success in the sciences is not itself rocket science. To be successful in the sciences, I first implore women to consider their motivation(s) and objective(s) in pursuing a scientific career. The path isn’t easy, and a firm sense of one’s self or a strong sense of ambition can help you become successful. Second, I remind women of the value of encouragement. I wouldn’t be where I am today without the love and support of my family as well as my friends. Third, I emphasize women to be patient and practice perseverance. You will have to pay your dues for a while, but eventually (if you don’t drop out), your hard work will pay off. Fourth, I highly recommend they learn a foreign language. Learning French and English really helped my career by allowing me to work outside of Cambodia. Fifth, but not least, I advise women to learn how to be independent.

I give this advice to young and older women looking for a career in the sciences. Science is not a study limited by age, and anyone has the ability to find something that helps someone.

Did you experience discrimination?

My culture is traditional, and I experienced discrimination as I pursued by scientific career goals. My male colleagues always asked why I continued to study medicine or pursue PhD, but I ignored them and focused on my goal: to be a doctor not only in my country, but worldwide.

Who do you look up to?

My grandmother is my role model. Despite Cambodia’s civil war and subsequent Pol Pot regime killing many doctors, she continued to study medicine in the capitol. Her hard work paid off, as today she is a successful gynecologist in Cambodia as well as a surgeon – a pretty rare feat for women in my country. One day, I hope to be as good of a doctor as my grandmother.